Coast to Coast

by Richard Hendrickson

The Journey of a Carload of Oranges from California to New York City aboard a Santa Fe Refrigerator Car in October of 1947

Railroad refrigerator cars revolutionized America's eating habits. Prior to the large-scale use of "reefers," fresh fruit and vegetables were available to people of ordinary means only for brief periods and only in and near the areas where they were grown. Many people in the northern two-thirds of the continent had never eaten an orange; some had never even seen one. Vegetables came in cans if at all, with most of their flavor and crispness cooked out of them, and lettuce salads were an unimaginable luxury. Long strings of refrigerator cars traveling east from the Pacific Coast and north from Florida and the Gulf Coast states changed all that, carrying fresh, ripe oranges, grapefruit, grapes, peaches, lettuce, and other products of field and grove to grocery stores in every part of the land. The Santa Fe Refrigerator Department was a pioneer in bringing this revolution about, operating for many years the second largest refrigerator car fleet in the world and rushing fresh produce eastward from California and Arizona in solid blocks of SFRD reefers, the renowned "GFX" trains (for "green fruit express"). In 1947 the Santa Fe owned almost 15,000 refrigerator cars, more cars than many class 1 railroads had on their entire freight car rosters. And those SFRD cars went almost everywhere on the North American rail network from Boston to Baltimore, New York to New Orleans, Saskatoon to Syracuse, Columbus, Ohio to Columbus, Georgia.

"Protective Service": Almost an Industry In Itself.

Providing what the railroads called "protective service" for perishables was, in its day, the most complicated aspect of rail transportation. Refrigerator cars themselves were costly to build and maintain and generally ran half of their mileage empty, though their owners sometimes succeeded in getting backhauls of clean merchandise. Insulation and ice bunkers took up much of their interior space, so their cubical capacity was smaller than that of a comparable boxcar. To maintain more or less constant temperatures while under refrigeration, they required frequent re-icing and sometimes the use of salt in the bunkers to promote lower temperatures except in winter, when charcoal heaters were often needed to prevent perishable cargoes from freezing. This meant that the railroads had to provide icing decks at frequent intervals, supervisors to manage them, and employees to staff them. In many cases, these ice decks also had to be supplied with ice and salt hauled from a considerable distance in non-revenue cars.

Shippers of different commodities (and sometimes of the same commodity) had different ideas about the features they wanted on reefers assigned to their use, so keeping track of how cars were equipped, where they were stored, and which shippers wanted cars of which type was a monumental task. Reefers also had to be thoroughly cleaned and inspected each time they were loaded. Then, because perishable prices fluctuated widely in the various regional markets, shippers were allowed to divert reefers en route from their original destination to locations, which might offer higher prices. Three such diversions per car were permitted without charge, and most shippers took fall advantage of this policy. Diversions alone, therefore, kept a small army of clerks busy at the keyboards of typewriters and Teletype machines.

Shippers of different commodities (and sometimes of the same commodity) had different ideas about the features they wanted on reefers assigned to their use, so keeping track of how cars were equipped, where they were stored, and which shippers wanted cars of which type was a monumental task. Reefers also had to be thoroughly cleaned and inspected each time they were loaded. Then, because perishable prices fluctuated widely in the various regional markets, shippers were allowed to divert reefers en route from their original destination to locations, which might offer higher prices. Three such diversions per car were permitted without charge, and most shippers took fall advantage of this policy. Diversions alone, therefore, kept a small army of clerks busy at the keyboards of typewriters and Teletype machines.

Despite all these problems, many railroads made money on reefer traffic - the Santa Fe certainly did - and went out of their way to provide shippers of perishables with the best possible service. In the heyday of the ice reefers, sixth or seventh day delivery from the West Coast to Chicago and ninth or tenth day delivery to the East Coast was provided for hundreds of carloads every day, week after week. Coast to Coast with an SFRD Reefer

To gain a better perspective on how perishable traffic was handled on the Santa Fe, I'm going to step back half a century in time and trace the journey of a single car in October of 1947 from Southern California to the shores of the Atlantic. In the most literal sense, the journey I'll be describing in words and pictures is fictional. But the description is based on a large body of historical information, documents, photographs, and personal reminiscences. It is typical of the transcontinental journeys made by countless Santa Fe refrigerator cars during the years between World War I and the 1960s when they transported much of the fresh produce consumed in North America from California and the southwest.

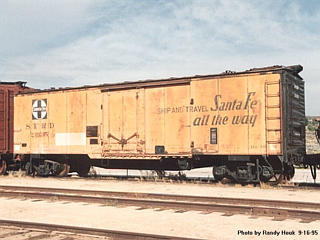

The car whose journey we'll be following was SFRD 32670, a Rr-23 class reefer. Originally one of thousands of modified USRA design wood-bodied refrigerator cars built for the Santa Fe in the early 1920s, it was rebuilt with an all-steel body by the Santa Fe's West Wichita shops in 1937. In September of 1946 it went back to West Wichita for repairs and repainting, emerging from the paint shop with a "Scout" slogan on the left side and billboard system map on the right. We pick up its trail a little over a year later, in early October of 1947.

Day -4 To tell the whole story of a typical reefer trip, we have to start several days before the car is loaded, with SFRD 32670 making its way toward San Bernardino in Extra 3852 west. This was an entire train of empty reefers being returned to Southern California for reloading. The Santa Fe made valiant efforts to generate westbound revenue traffic for its reefer fleet. Going so far as to offer shippers in the east and Midwest two cars for the price of one if they would ship westbound loads in reefers rather than box cars. But these efforts were never more than partly successful and most SFRD cars came back empty, one reason why refrigerator car operations were so costly.

Day -3 After arriving in San Bernardino, hub of the Santa Fe's operations in Southern California. SFRD 32670 was switched to one of the reefer tracks adjacent to the car shops at the east end of "A" yard, where it was thoroughly steam-cleaned inside and any needed minor repairs were carried out. It was then inspected, tagged as fit for loading, and switched to an outbound reefer storage track. Meanwhile, in the small town of Escondido, near San Diego, on the Fourth District of the Los Angeles Division. The Santa Fe agent received an estimate of the number of cars required in the next several days by the Escondido Orange Co-Op packing house and transmitted it by wire to the Refrigerator Department office in San Bernardino.

Day -2 As one of the empty cars assigned for delivery to the Escondido Orange Co-Op, SFRD 32670 was pulled from a storage track and moved in the late afternoon to a make-up track in the San Bernardino yard. By nightfall it had become part of a nightly train bound for San Diego, the "SDX," consisting mostly of empty reefers and loaded merchandise cars. Powered by 2-8-2 3142, this train eased out of San Bernardino, across the Southern Pacific diamond at Colton, and west on the Third District mainline via Riverside, Corona, and the Santa Ana River canyon. At Atwood, Extra 3142 swung left onto the Olive Branch to Orange, then left again onto the Fourth District main line toward San Diego, often called the Surf Line because much of it ran along the Pacific only yards away from the ocean beaches.

Day -1 In the early hours of the morning. Extra 3142 ground to a halt in the small yard at Oceanside. A cut of empty reefers, including SFRD 32670, was uncoupled from the train and left on an adjacent yard track. The 3142 then barked out of town with the rest of its train bound for the tough climb up Linda Vista grade and pre-dawn arrival in San Diego. At 5:30 a.m. one of the firemen on the two local trains that operated out of Oceanside came down to the engine track and lit fires in both of the 2-8-2s that were simmering there nose to nose, then went home to breakfast. By 8:00 a.m., with steam pressure up in the engines, the two local crews arrived to switch the yard and make their daily rounds on the Fallbrook and Escondido branches. Power for the Escondido train was the 3155, and its train consisted of an LCL car waybilled to Vista, a box car loaded with lumber for Escondido, and a long string of empty reefers for the packing sheds in both towns. After a brief pause while the morning San Diegan streamliner made its station stop and thundered off towards San Diego, the local crew finished assembling second class freight train number 66. Rattled the slack out of its 34 cars, and headed out on the main, through the Escondido Junction wye, and eastward along the river valley. Dropping a block of cars at Vista to be switched later, the 3155 arrived at Escondido just after noon and the crew "went for beans," then turned the engine on the wye and began switching the lumber yard and packing sheds. Meanwhile, in the groves a few miles away, ripe oranges were being picked and loaded on trucks bound for the Escondido Orange Co-Op. By late afternoon, all the loaded reefers had been pulled from the two spurs at the Co-Op and SFRD 32670 had been spotted, along with nine other empty cars, in their place. Its chores at Escondido completed, the 3155 then departed on the trip back to Vista and Oceanside.

Day 1 Working with practiced efficiency, the Orange Co-Op crew began loading SFRD 32670 with wooden boxes of navel oranges stacked on end. At the same time, 300 lb. blocks of ice from the adjacent ice plant were being brought across on an overhead cable and dropped into the bunkers. By late afternoon, the car was loaded and iced, the doors were sealed, and it was ready to roll, billed to a produce wholesaler in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Day 2 Train 66, with the 3155 in charge again, arrived in Escondido around mid-day and its daily switching routine was repeated. SFRD 32670 left town as part of train 67 westbound, arriving at Oceanside in the early evening. One of a string of loaded reefers left on the No. 1 yard track by the local crew, it sat for several hours with water quietly dripping from its bunker drains until just before midnight. When the distant sound of a deep-throated whistle announced the arrival of the nightly "SBX" from San Diego to San Bernardino, Extra 4027 west.

Day 3 With SFRD 32670 and the other Oceanside reefers coupled on to the head end of its train, big 2-8-2 4027 rumbled up the coast. Then across the Olive branch to Atwood, and - running now as Extra 4027 east - towards San Bernardino on the Third District, arriving in "B" yard as the sky began to lighten in the east. The loaded reefers, SFRD 32670 among them, were switched to the pre-cooling plant, where cold air was blown into them through open hatch covers for several hours to remove field heat from their loads. They were then moved to the adjacent ice deck to have their bunkers topped off. Then shunted to an outbound track for journal oiling and inspection. Road engine 3858 and two other husky 3800 class 2-10-2s were brought down from the roundhouse and by early afternoon "GFX" extra 3858 east with 68 loaded reefers was waiting for a highball. A whistle signal from the 3858 alerted the crews of the helper engines, the slack came in, and Extra 3858 rolled through the wye into "A" yard and charged past the passenger depot, all three locomotives already wide open and getting a run at the hill. After laboring up Cajon Pass at ten to fifteen miles an hour, with a twenty minute stop to take water at Keenbrook, Extra 3858 crested the hill at Summit and the helpers were cut off to run light back to San Bernardino. Air test completed, the 3858 then took off down grade into the Mojave Desert through Victorville to Barstow. There, with late afternoon shadows lengthening, the 3858 chuffed off to the roundhouse and was replaced by four FT diesels, 132L-A-B-C, standard power on the arid Arizona Division. Slowly at first, until clear of the Union Pacific junction at Daggett, then faster across the barren desert, 132L chased its headlight beam through Ludlow and Cadiz, up the grade to Goffs, and down into the Colorado River valley at Needles.

Day 4 In the early hours of the morning, SFRD 32670 and the other cars of Extra 132 east were drawn up alongside the Needles ice deck while ice thumped and rattled into their bunkers. A sheaf of papers in the hands of the deck foreman spelled out the individualized icing instructions for each car. Then a new engine crew picked up its clearance card, climbed into the cab, tested the air, and rumbled out of town for the long steady climb east, to the end of the division at Seligman. With dawn breaking. Extra 132 east continued on to Ash Fork, Williams, Flagstaff, and Winslow. At Winslow, the 132 was replaced by four-unit 137L-A-B-C, another set of the FT's delivered during World War II. In summer, the cars would have been iced again at the Winslow ice deck, but re-icing wasn't necessary after a night run across the desert in October so the GFX continued east after a brief stop, following the Albuquerque Division's double-track main line into New Mexico. Gallup came and went, the sun declined in the west, and at Dalies the train swung right onto the Belen cutoff for a brief run down the New Mexico Division's El Paso Line and then left into the big yard at Belen. Time for another sojourn at the ice deck while the temperatures in the cars were checked, the bunkers were re-iced, and the car oilers and inspectors made their rounds.

Day 5 Engine 5003, one of the Santa Fe's huge 2-10-4s, backed down to a coupling. Replacing the FT's, and soon the floodlights of Belen yard were fading in the distance as "GFX" Extra 5003 east raced across the Pecos Division at fifty to sixty miles an hour en route to Vaughn and Clovis. At Clovis, cars billed to Texas and Southeastern destinations were cut out and some reefers from stations in New Mexico and West Texas were added, along with several loaded stock cars, which were cut in directly behind the engine. Then it was off at a gallop to Amarillo for a brief water stop and crew change and onward onto the Plains Division. Across the Texas Panhandle into Oklahoma the 5003 put mile after mile under its 74 inch drivers as night fell, until the lights of the Santa Fe's division point and yard at Waynoka appeared on the horizon. Extra 5003 came to a halt alongside the ice deck for another round of icing and inspection. Meanwhile, produce prices in Pittsburgh had declined, so a diversion order was dispatched on the Santa Fe's company wires re-directing SFRD 32670 to the produce market in Detroit.

Day 6 Several of the Santa Fe's 3765 class 4-8-4s, recently bumped from transcontinental passenger service by the delivery of new diesel locomotives, had been assigned to fast freight service across the flatlands of Kansas. It was engine 3768 that emerged out of the darkness at Waynoka and coupled on to the eastbound GFX. Few railroads used 4-8-4s with eighty-inch drivers in freight service, but then, few railroads ran freight trains Santa Fe style. Ten year old 3768 bellowed out of Waynoka with SFRD 32670 and seventy-two other cars trailing behind and set out across the Panhandle Division to Wellington. Then north to the double track Middle Division main line and east via Emporia and Ottawa Junction on the Eastern Division to Kansas City, arriving after nightfall at the Santa Fe's vast Argentine Yard. Once again, it was time for the ice deck crew and the car inspectors to do their work. The stock cars came off the head end and were switched to the Kansas City Union Stock Yards and some reefers bound for St. Louis were cut out of the train to be handed off to the Missouri Pacific. SFRD 32670, however, continued onward towards Chicago.

Day 7 By midnight the re-shuffled GFX was ready to roll again behind the 4108, one of the Santa Fe's fifteen coal-burning 2-8-4s that were built in 1927 specifically for fast freight service on the double-tracked Missouri Division. Extra 4108 made it's way eastward to Marceline, then across the southeastern tip of Iowa for a quick stop at Ft. Madison. The train was then turned over to coal-burning 2-8-2 3266 for the final lap across the Mississippi onto the Illinois Division and on through Galesburg, Streator, and Joliet to Corwith Yard in Chicago, "Santa Fe All the Way" for more than 2,000 miles from SFRD 32670's starting point in Escondido. Meanwhile, another diversion order changed the car's destination again, this time to a broker in New York City, where orange prices were expected to remain strong for the next several days.

Day 8 Picked up from Corwith by an Indiana Harbor Belt interchange crew with a typically grimy IHB 2-8-2. The block of eastbound reefers that included SFRD 32670 slowly threaded its way through the tangled maze of railroad tracks in the Chicago Switching District to Blue Island yard. Where the cars were iced again, and then across the Indiana border to a connection with the Erie Railroad at Hammond, Indiana. Here the SFRD reefers became a part of the Erie's nightly perishable express "NY-98" and by early evening they were eastbound behind engine 3356, one of the handsome and competent fast-freight 2-8-4s built by Baldwin for the Erie in 1928.

Day 9 Eastbound through the night, "NY-98" made its way across Indiana and Ohio, past the division point at Marion, and on into New York. By late afternoon, the train was stopped alongside the ice deck at Hornell, NY while the cars were inspected and re-iced. Then it was off again towards the east.

Day 10 In the middle of the night "NY-98" threaded its way through the yard at Port Jervis and rumbled onward to Campbell Hall, New York, where some reefers bound for Boston were cut out and handed off to the New Haven. Then it turned south into New Jersey and headed for the Erie's Croxton Yard west of Jersey City. As morning came, switchers descended on the arrival track where "NY-98" had come to rest and began moving its reefers to their various destinations. For SFRD 32670, this meant a short run to the Erie's Jersey City marine terminal, where it became one of the cars loaded on a barge. In the late afternoon a steam tug with the Erie's diamond herald on its tall funnel came alongside, lines were made fast, and the barge was maneuvered out into the Hudson River and across to the Erie's produce piers in Manhattan, where it was tied up alongside other barges. A door seal was broken, the door opened, and samples of the car's load were taken out to be displayed at the next morning's auction.

Day 11 The fruit auction at Piers 21-22 started early, and before the sun was up the oranges in SFRD 32670 had been purchased by the Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company. Soon the oranges from Escondido were being loaded into A&P trucks and carted off to retail stores in the New York City area. Some of them became part of a truckload to be delivered to an A&P food store in the Long Island suburb of Brooklyn, where by late afternoon they had been uncrated and placed on display in the produce section.

Day 12 Mrs. June Levy, shopping at her neighborhood A&P store in Brooklyn, bought a half-dozen oranges, took them home, and arranged some of them in a fruit bowl on her dining room table. In doing so, she reflected that in her childhood, not so many years ago, fresh oranges were a rare and expensive treat. Meanwhile, SFRD 32670 was barged back to Jersey City and returned to Croxton Yard, where it was switched into a westbound freight train for the return trip to California. Conclusion

Eleven days to cross the continent, less than two weeks from tree to table - that was the kind of ice-refrigerated perishable service the Santa Fe and its partners delivered day in and day out a half century ago. It took a lot of resources, a lot of manpower, and a lot of the fast running for which the Santa Fe was widely celebrated. It would be a notable achievement even today, in the era of mechanical refrigeration, roller bearings, radios, and 4,400 horsepower diesel locomotives. Fifty years ago, in the days of steam locomotives, telegraphed train orders, and ice refrigeration, it was truly remarkable.

Back to the Story Page

Back to the Story Page