Thomas Fielding Retires After 45-Year Career

RETIRING November 30 after 45 years of railroading was Thomas Fielding, traffic manager of the San Diego

and Arizona Eastern Railway Company and district freight and passenger agent for Southern Pacific,

with headquarters in San Diego. He had held these posts since 1941.

RETIRING November 30 after 45 years of railroading was Thomas Fielding, traffic manager of the San Diego

and Arizona Eastern Railway Company and district freight and passenger agent for Southern Pacific,

with headquarters in San Diego. He had held these posts since 1941.After ten years' experience with Colorado railroads, Fielding joined our company in Los Angeles as a clerk in 1921. He advanced to city freight agent in 1922, asst. industrial agent in 1937 and district freight agent in 1938.

Fielding has been active in numerous civic and chamber of commerce projects throughout San Diego County and is a former director of San Diego C. of C.

W. D. Keller Receives San Diego Promotion

EFFECTIVE December 1, Willard Keller was appointed traffic manager of the San Diego & Arizona

Eastern Railway Company, and district freight and passenger agent for Southern Pacific.

EFFECTIVE December 1, Willard Keller was appointed traffic manager of the San Diego & Arizona

Eastern Railway Company, and district freight and passenger agent for Southern Pacific.Keller began his railroading career in 1914 when he joined the Los Angeles General Freight Office. By 1926 he had risen to city freight agent and in 1938 was appointed traveling freight agent.

From 1942 to 1948 he was district freight and passenger agent at El Centro. In 1948 he was appointed district freight agent, with headquarters in Los Angeles, serving in that capacity until January, 1955, when he rose to be assistant general freight agent of the Los Angeles District.

February, Page 47

OUR SYMPATHY

MISCELLANEOUS

Thomas O'Connell, master mechanic, SD&AE.

March, Page 38

SD&AE Railway

Head Reporter: Floy Richmond.

CFA Jack Wilkinson was elected president of the Transportation Club of San Diego for year 1957 and also elected secretary-treasurer of the new chapter of Delta Nu Alpha Transportation Fraternity, Inc. . . . Secretary Floy Richmond went to Phoenix to attend the chapter party of Phoenix Chapter of Executives' Secretaries.

April, Page 27

GIVEN AWAY last month was the "Grand Old Lady of Imperial Valley Railroading," locomotive 2353, when she was dedicated as a memorial at the California Mid-Winter Fair. Imperial Valley will keep her, and she will rest there where she worked so well. Leo Ford, right, our DF&PA at El Centro, presents a silver spike to J. R. Snyder, president of the fair board, in the ceremony.

GIVEN AWAY last month was the "Grand Old Lady of Imperial Valley Railroading," locomotive 2353, when she was dedicated as a memorial at the California Mid-Winter Fair. Imperial Valley will keep her, and she will rest there where she worked so well. Leo Ford, right, our DF&PA at El Centro, presents a silver spike to J. R. Snyder, president of the fair board, in the ceremony.

April, Page 45

THANKS TO YOU

Deserving Happy Retirement

MISCELLANEOUS

John Fielder, Machinist, SD&AE.

June, Page 14, 15, 16

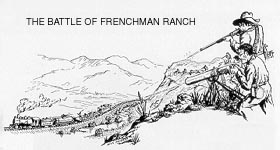

The War That Ended in a Railroad Caboose!

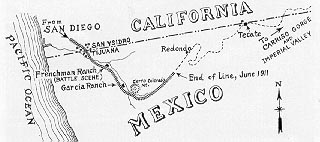

FORTY-SIX years ago this month a war in Mexico ended with surrender aboard a railroad caboose. The railroad is now our San Diego & Arizona Eastern. As setting for the ceremony, the late Conductor W. G. McCormick and crew of the then San Diego and Arizona Railway (the "Eastern" was added in 1933) halted their bullet-scarred train with its tail-end over the international boundary. There, where efficient customs officers inspect our trains today, "General" Mosby laid his guns on the caboose table at noon, June 22, 1911, ending the bloody attempt by his I.W.W. army (International Workers of the World) to take Baja, California, from Mexico by insurrection and to set up their own government there. Six weeks of thrills and neardeath ended then for the railroaders. Direct action had been taken by Sport, their bulldog mascot - who nearly got one of the insurrectionists by the seat of the pants - but otherwise the railroaders had saved themselves and company property only by sustained courage and bluffing. With the exception of Sport, it was no fun for anyone-especially the insurrectionists who were killed in the last battle aboard the train. Their unmarked graves lie within a few feet of the rails that now carry our SD&AE freight trains on their daily swings of 71.4 kilometers into and out of Mexico en route between San Diego and the Imperial Valley. The insurrection was one of several headaches suffered by the sugar king J. D. Spreckels in his attempt to build his "impossible" railroad through the Carriso Gorge. SP assisted him in finishing the job, and bought out the Spreckels interests in 1933.

War Is Declared

General Price, another of the I.W.W. insurrectionists, declared, "Spreckels has millions and large interests in this section. It is my intention to make him and other large holders contribute heavily to the support of my army." Against Generals Price and Mosby and several hundred of their army, Conductor McCormick and crew, including Sport, pitted their wits.

Wires Are Cut

On May 8 the insurrectionists began cutting telegraph wires along the railroad to hide their attack on Tijuana. They killed the mayor the following day, burned the church and bull ring and chased most of the residents across the border into the United States. Next day General Price put his men aboard the construction trains to be sure the railroaders remained neutral as the trains went south through Tijuana to where the railroad forces were laying rails near Redondo Valley, headed toward Tecate. Soon the insurrectionists were demanding and taking railroad supplies from the trains, giving "receipts" in return. It was at this time that Sport, apparently skeptical of the receipts, attacked Quartermaster Melford.

Trains Are Raided

On May 19 the insurrectionists went so far as to raid the work camp and take possession of the train, but Conductor McCormick got them out of the camp by fast talking and took his train back safely to San Diego, where Chief Engineer E. J. Kallright advised him against trying to oppose the insurrectionists so vigorously. Kallright quoted Spreckels as saying he would rather lose everything in Mexico than have one of his employes get killed. Conductor McCormick told him not to worry. On May 24, General Price arrested a party of railroad workers and held them in jail overnight in Tijuana. McCormick talked them free in the morning.

General Skips Out

Five days later General Price collected a substantial sum of money from supporters, and skipped out with the cash. The insurrectionists then asked a Captain Smith to take charge, but he refused; and Captain Mosby came to take command, although recently wounded in a battle at Tecate. He was given the title of general, but was unable to control his forces. The insurrectionists began to shoot at the trains. Quartermaster Melford seized more supplies. More laborers were arrested. Mosby took most of his forces and headed for Ensenada, leaving only a token number to protect Tijuana, but he fled back when he learned that 1,400 Federals were approaching. In order to avoid international complications, Mosby commandeered McCormick's train and headed south with 128 men to stage the battle as far from the United States as possible. McCormick and crew luckily were not forced to go. Baled hay was piled on the flat car as a barricade, but along the river bottom near Frenchman's Ranch the bales proved of little protection as the Federals suddenly opened fire with machine guns from hills towering over the tracks. The slaughter was terrific. (After the battle the Federals reported that they buried 21 of their own men.) Mosby and his few survivors raced their train madly back to Tijuana and asked if they could surrender to the American forces massed just across the border. This was arranged for, with Mosby in the Mexican end of the caboose and Captain Wilcox of the United States Army in the other. The insurrectionists were in terror, fearful of the Federals. The surrendered guns remained on the table of the caboose, souvenirs of "our" war. We'll tell you more about this interesting railroad, the San Diego & Arizona Eastern, in a later issue of The Bulletin.

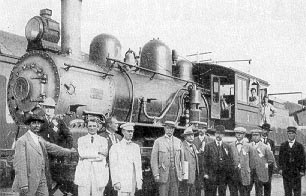

Engine No. 1 of the San Diego and

Arizona Railway and some of the men who saw her through an

insurrection in Baja California in 1911, pictured as they looked then. On the pilot, two white tags on

his coat, is Conductor W. G. McCormick, who fought the insurrectionists with bluff. Front center in

straw hat stands John D. Spreckels, who was financing the railroad at that time. Other in straw hat

is E. J. Kallright. chief engineer, who located and constructed the railroad and placed it in operation.

Between them stands H. L. Titus, first general manager.

Engine No. 1 of the San Diego and

Arizona Railway and some of the men who saw her through an

insurrection in Baja California in 1911, pictured as they looked then. On the pilot, two white tags on

his coat, is Conductor W. G. McCormick, who fought the insurrectionists with bluff. Front center in

straw hat stands John D. Spreckels, who was financing the railroad at that time. Other in straw hat

is E. J. Kallright. chief engineer, who located and constructed the railroad and placed it in operation.

Between them stands H. L. Titus, first general manager.

July, Page 15

THIS HISTORIC PICTURE was unearthed by one of our retirees, Frank C. Heath of Comptche, California, after he read our article last month on "The War That Ended in a Railroad Caboose." It shows the insurrectionists commandeering the San Diego & Arizona Railway train in which their ill-fated adventure died, June 22, 1911. Frank, like the hero of our true story, the late W. G. McCormick, was a conductor on the old SD&A, now our San Diego & Arizona Eastern.

THIS HISTORIC PICTURE was unearthed by one of our retirees, Frank C. Heath of Comptche, California, after he read our article last month on "The War That Ended in a Railroad Caboose." It shows the insurrectionists commandeering the San Diego & Arizona Railway train in which their ill-fated adventure died, June 22, 1911. Frank, like the hero of our true story, the late W. G. McCormick, was a conductor on the old SD&A, now our San Diego & Arizona Eastern.

July, Page 29

The SD&AE-SP bowling team beat the airlines, bus lines, other rail-roads-in fact, all other seven teams in the San Diego Passenger Association League - to capture the second half of the league's 1956-57 schedule, and then won the play-off for the league championship for the year, beating American Air Lines by 16 pins. All members of the SD&AE - SP team raised their averages this season.

September, Pages 14,15,16,17

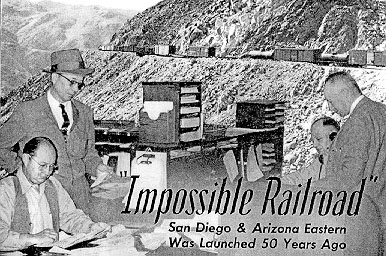

"Impossible Railroad" San Diego & Arizona Eastern Was Launched 50 Years Ago

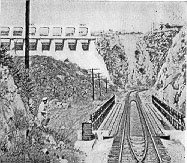

(Photo Left)These men in the dispatcher's office of the SD&AE at San Diego

probably have in their minds a picture of the so-called "impossible railroad" shown in the background, as they prepare for departure of a train

soon to be on that rugged track. Standing, left to right, are Jerry L. Green, trainmaster, and Carl M. Eichenlaub, superintendent.

Seated, Gerald J. Wolfe, train-master's clerk, and Albert A. Wyttenbach, telegrapher. The background scene is a portion of the

Carriso Gorge, through which men once declared construction of a railroad was impossible.

(Photo Left)These men in the dispatcher's office of the SD&AE at San Diego

probably have in their minds a picture of the so-called "impossible railroad" shown in the background, as they prepare for departure of a train

soon to be on that rugged track. Standing, left to right, are Jerry L. Green, trainmaster, and Carl M. Eichenlaub, superintendent.

Seated, Gerald J. Wolfe, train-master's clerk, and Albert A. Wyttenbach, telegrapher. The background scene is a portion of the

Carriso Gorge, through which men once declared construction of a railroad was impossible.FIFTY years ago this month, September, 1907, the first spike was driven on an "impossible" railroad, now the San Diego & Arizona Eastern, a wholly owned part of our Southern Pacific.

Head man at the scene of operations is Superintendent Carl M. Eichenlaub, born in San Diego and forever in love with his city. As a boy he hunted rabbits on Otay mesa across the border in Mexico, and looked down from the mesa to watch herds of wild horses digging for water in the stream bed near which the track now runs.

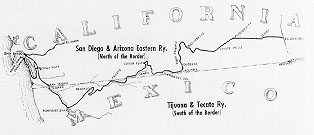

The San Diego & Arizona Eastern owns a subsidiary, the Tijuana & Tecate Railway, which has title to a 44.4-mile portion of track in Mexico. Combined, they give us an international route running from San Diego southward across the border into Baja California, and climbing back again through a wild world of rocks to Tierra Del Sol at 3,660 feet elevation, then through tunnels and over trestles clinging to the side of spectacular Carriso Gorge, and down through a gray desert into the green Imperial Valley, which is below sea level.

The main line, between San Diego and El Centro, including the Tijuana & Tecate, is 147.5 miles long, "Shortest and fastest rail route east from San Diego," as Willard D. Keller, traffic manager, points out. "Through rates are applicable." Eastward from El Centro in Imperial Valley, train operations are handled by Southern Pacific.

The San Diego & Arizona Eastern was one of the last pieces of heavy railroad construction in the United States, and one of the most difficult railroads to build. It is also one of the most spectacular, especially in late winter or early spring when the fields of Mexico are bright green and sprinkled with wildflowers.

(Photo below)Beyond a framework of poinsettias we see a switch engine making up our freight train.

Let's Ride a Freight!

Let's Ride a Freight!

Let's imagine we are boarding a train for a ride over this amazing route in spring when the country is at its best.

It will be a freight train, because all through passenger service was abandoned in January, 1951. Fast highways

drained away the passenger traffic.

The early morning sun brightens the last poinsettias still blooming beside the San Diego yard office as a

switch engine makes up our train. (The railroad operates one 900 - horsepower, three 660-horsepower and

four 1,600-horse-power locomotives leased from SP.)

Engineer Ed M. Marshall eases the throttle open and we are on our way!

For a while we will have easy, almost level running, with a rul-ing grade of 1.4 per cent to be expected later

as we climb over the mountains. (Coming back it would be tougher, as much as 2.2 per cent in some places.)

As we head southward at 20 miles an hour, then step up to 30, we see a number of industrial plants,

including large aircraft factories, sprawled on the flat lands stretching between us and the coast.

In the outskirts of National City the friendly hooting of our engine warns automobiles to stop short

of the crossings. At one point, children are too close to the track for Engineer Marshall's peace

of mind. He keeps his hand on the brake until they move back - and he makes a mental note to notify their

parents that railroads are no place for playing!

Our wheels clatter over the Chula Vista crossing.

The Chula Vista branch of the SD&AE is one of several branches fingering out into the neighboring industrial

and agricultural areas. These branches are mostly the remains of three railroads which already were in existence

50 years ago - the Coronado Railroad, which ran around San Diego Bay to Coronado; the National City and Otay

Railway, which ran from San Diego to Otay and on to San Ysidro at the international border; and the San Diego

and Cuyamaca Eastern, which ran to Foster near where the San Vicente dam is now located.

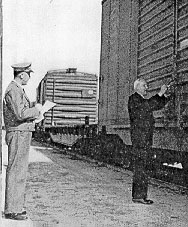

(Photo left)Customs Inspector J.T. Hicks, left, watches

as B.D. Cornell, telegrapher-clerk, seals a car before it crosses the border into Mexico.

(Photo left)Customs Inspector J.T. Hicks, left, watches

as B.D. Cornell, telegrapher-clerk, seals a car before it crosses the border into Mexico.

To Provide Direct Link

The new railroad was not intended to compete with these local lines, but to provide a direct railroad to

the east. Those three railroads, which were only local carriers, were taken in later as branch lines of

the present company.

(Photo left) Beyond the fence is another country.

We'll take you there in the columns of your magazine next month as we continue our ride toward

Imperial Valley on an SD&AE freight train.

(Photo left) Beyond the fence is another country.

We'll take you there in the columns of your magazine next month as we continue our ride toward

Imperial Valley on an SD&AE freight train.

Growing Rapidly

The area stretching out for miles in all landward directions from San Diego - with its half million people - is

growing rapidly in population and industry. At the harbor - dredged in World War II to handle ships of

any size - a $10,000,000 pier and transit shed project is under way. A huge oil refinery in prospect

is expected to reduce the present oil price differential, and thus encourage more ships to fuel at San Diego.

The ocean-going freighters bring such important loads as phosphates from Finland and Norway, to be

hauled over into Imperial Valley by the SD&AE and used as fertilizers. Outbound, the ships take

cotton hauled by the SD&AE out of Imperial Valley, mostly from the Mexicali area.

We Serve Many

The Naval Air Station at North Island is served exclusively by the SD&AE. Extensions of track on the

El Cajon branch are contemplated by the SD&AE to serve various plants and new industrial areas. Celery,

citrus and other perishables are raised along the Chula Vista branch, and hauled by this rail road. A large

plant for making salt from sea water is located on that branch.

This morning, our train has nine cars of construction steel to set out at San Ysidro. After making the

setout we stop short of the steel gate which blocks our track at the international border. There our

cars are inspected and sealed under direction of J. T. Hicks, customs inspector, before the gate is

swung open and we cross into Mexico.

The gate is closed and locked behind us.

(Next month, in the Bulletin, our ride will continue south of the border.)

October, Page 28,29,30

Under Two Flags - Tijuana and Tecate Carries S.D.&A.E. Trains in Mexico

(Continued -from last month) AFTER our SD&AE freight train arrives in Tijuana, en route between

San Diego and Imperial Valley, it becomes for the next few hours a part of our Tijuana & Tecate Railway.

(C. L. Lay is assistant general manager under J. B. Burdick at Mexicali.)

(Continued -from last month) AFTER our SD&AE freight train arrives in Tijuana, en route between

San Diego and Imperial Valley, it becomes for the next few hours a part of our Tijuana & Tecate Railway.

(C. L. Lay is assistant general manager under J. B. Burdick at Mexicali.)

Strange Caboose

In Mexico we carry passengers. They are one reason we are hauling the type of "caboose" that was coupled

onto our train in San Diego. It is lettered as a baggage car, and contains in its forward end a sealed

compartment for express.

In the middle portion are conventional caboose stove, desk and other equipment for Conductor Fred Johnson.

Rear third of the car is a passenger section of coach seats for the Mexicans who board the train at Tijuana,

and who must leave again before we cross back into the United States beyond Tecate.

Our Spanish is rusty, and all we can understand are the "Gracias!" and the warm smiles.

It is springtime. Through the green fields of Tijuana Valley, irrigated by the waters from behind the

great Rodriquez Dam, we roll deeper into Mexico. The mileposts have become kilometer posts.

It was in this vicinity that the insurrectionists of 1911 (see The Bulletin for June) gave the

railroad builders a bad time.

The men who did most to overcome the difficulties of the insurrection and of the rugged country were

John D. Spreckels, son of the "sugar king," and E. J. Kallright; chief engineer of construction.

History Reviewed

The J. D. and A. B. Spreckels Company came into the picture at the start, in response to pleas from

San Diego for a direct rail line east, and brought about the incorporation of the San Diego & Arizona

Railway on December 15, 1906. Under direction of the Spreckels Company, about 68 miles of the San Diego

end of the line was laid after driving of the first spike.

The Spreckels interests also built the portion from Seeley westward, part of which - Seeley to Coyote Wells - was

for a time leased to the Holton Inter-Urban Railway.

The Southern Pacific Company built the track between El Centro and Seeley which was opened for traffic on

August 29, 1910. This section of track was leased to the Holton Inter-Urban Railway during the period

January 1, 1916 to April 4, 1917, and on December 1, 1919, was leased to the San Diego & Arizona Railway.

On February 1, 1933, Southern Pacific bought out the remaining Spreckels interests and changed the name

to San Diego & Arizona Eastern.

(Photo left)At the famous brewery in Tecate our locomotive performs some switching

before taking our train - standing at the left - on toward Carriso Gorge and the Imperail Valley.

(Photo left)At the famous brewery in Tecate our locomotive performs some switching

before taking our train - standing at the left - on toward Carriso Gorge and the Imperail Valley.

Meet Eichenlaub

Chief Engineer Kallright had been one of the trusted assistants of Chief Engineer William Hood of the

Southern Pacific. To join his staff as office boy in 1914 came young Carl Eichenlaub, who - although

he had been crippled in an accident at the age of 13 - worked his way through school to become an

engineer and take charge of the drafting room in 1918. Now, as superintendent, he not only is top

operating man on the ground but has the longest service record of anyone in the railroad.

As our train leaves the Tijuana Valley and plunges into the first of the many tunnels, any doubts we

may have had about the quality of construction are dispelled by the sight of the stone portal, expertly

designed and cut.

(Photo left)Towering Rodriquez Dam our train rolls smoothly across

one of the stout bridges in Mananuca Canyon.

(Photo left)Towering Rodriquez Dam our train rolls smoothly across

one of the stout bridges in Mananuca Canyon.

Emerging from this tunnel into Matanuca Canyon we pass close below the towering Rodriques Dam, constructed

in 1928, and roll across a bridge sounding firm and smooth beneath our wheels.

From Redondo Valley, which was end of the line at the time the insurrectionists waged their war the track

sweeps to the right and then to the left in two great climbing, horseshoe curves to the south above the

green valley, with San Ysidro Mountains rising in misty grandeur opposite to the north.

Huge Boulders

Our diesels are pulling hard, and wheel flanges squeal on the rails. But the pace is slow enough for us to enjoy

the red sweet peas among the green, the splashes of buttercups and poppies, the lupine, wild lilac,

buckwheat, chemise, sage and elderberry. And among them all, as though tossed wildly in the days of

Creation, lie gigantic granite boulders, some of them higher than the train.

Drafted by Carl

Beyond the curve at Indian Joe's we see the remains of what was once a railroad siding. This was end-of-track

when Carl joined the railroad. From here on he laid out much of the line on his drafting board.

Near La Puerta we duck under a modern highway overpass, on the main road between Tijuana and Tecate. Soon

after, we roll into Tecate, and our diesels switch cars at the famous brewery. Barley for the brewery

is brought here from central United States and from Canada-delivered by the SD&AE, of course.

Back Into USA

At Lindero our train plunges into Tunnel 4 and makes an underground entry back into the United

States (see The Bulletin for May), emerging over Campo Creek and into Campo, where the cars

are again checked by customs inspectors to make sure the seals were not broken in Mexico.

Rabbit merchant of Tecate

Rabbit merchant of Tecate

(Look for the final installment of the SD&AE story in next month's issue)

November, Page 16

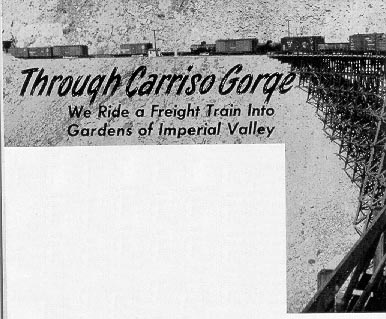

Through Carriso Gorge, We Ride a Freight Train Into Gardens of Imperial Valley

(Concluding SD&AE freight train ride description from last month's Bulletin.)

(Concluding SD&AE freight train ride description from last month's Bulletin.)

(Photo at left)Rolling across highest trestle on our SD&AE, a freight train passes one of the

line's two block signals and slips into one of many tunnels in the Carriso Gorge.

BRIDGES, tunnels and track are spectacular on the route of our SD&AE, especially

after our train turns back northward into the United States from Mexico, en route to

Imperial Valley.

A second crossing of Campo Creek is made on a viaduct 175 feet above the stream bed,

and now we climb through wildly rocky country to Tierra Del Sol, where we move into

a siding and allow a San Diego-bound train to pass.

Near Round Mountain the railroad serves Jacumba. This was a meeting place for the

Indians long before the advent of white men. The hot springs are still used for

their curative powers.

At Dubbers we push two cakes of ice out of the door of the express end of our "caboose,"

to cool the food of B&B forces stationed there.

Balancing Rocks

On the mountainsides red granite is mixed with the gray, in tortured shapes and tumbled

masses. It is said that during the Cretaceous Age there was a widespread eruption of molten rock that overflowed a large portion of San Diego County.

This molten rock cooled to a species of granite and the looser stuff was gradually

carried away by water, letting the harder boulders settle down on top of one another.

So strange in appearance is this area that it has been proposed as a National

Balancing Rocks Monument.

This is the entrance to the famous Carriso Gorge, where the track winds along steep

rock slopes on a manmade shelf nearly a thousand feet above the bottom of the canyon.

Sixteen tunnels were bored through the granite in the 11 miles of the Carriso Gorge track. Two of the tunnels have since been by-passed.

High Trestle

We emerge from Tunnel 15 onto a timber trestle of dizzying height, built to by-pass

a slide in the winter of 1932. The trestle rises 185 feet from its lowest foundations.

Superintendent Carl Eichenlaub can tell you the location of every brace. He was chief

draftsman when the structure was designed.

At either end of this tall trestle are block signals connected to warning devices

which will automatically cause the signals to show a "Stop" indication if the trestle

is on fire or if damage has been caused by falling rocks.

Many other trestles cling to the rock of the gorge. In some places they support only

the outer rail, while the inner rail is supported by the rock itself.

These timber structures were a constant worry in the days of steam engines. With

diesels there are fewer sparks. The high trestle at Tunnel 15 is equipped with a

water system for fire fighting, the water being supplied from a reservoir filled

periodically from tank cars, but the water system has not been called into

action since the steamers were replaced with diesels.

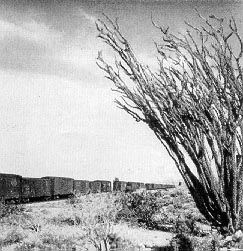

(Photo at left) At Dos Cabezas our train stops to pick up a car. The large ocotilla cactus is bright

with red blooms.

(Photo at left) At Dos Cabezas our train stops to pick up a car. The large ocotilla cactus is bright

with red blooms.

Track Wear Reduced

Also, since the coming of diesels, and the discontinuing of passenger trains,

track wear has been greatly reduced.

There is almost no vegetation in Carriso Gorge, except a grove of palm trees at the very bottom.

Grass grows in the depths, and it is from this grass that the gorge gets its name. The grass was used by the Indians in making baskets.

Appropriately, it was in Carriso Gorge that John D. Spreckels chose to drive a $286

gold spike into a tie on December 1, 1919, to mark completion of the rail line. This

railroad, which we helped him build, and to which we bought full title in 1933, had

been considered so important that it was the only railroad released from federal

control during World War I so its construction could be finished.

(Photo at left) Another view of the high trestle at Tunnel 15, photographed shortly after it was completed.

It bypassed a slide which weakened the former tunnel, whose portal is visible beyond.

Some of the "specks" on top of the trestle, in front of the abandoned portal, are workmen.

(Photo at left) Another view of the high trestle at Tunnel 15, photographed shortly after it was completed.

It bypassed a slide which weakened the former tunnel, whose portal is visible beyond.

Some of the "specks" on top of the trestle, in front of the abandoned portal, are workmen.

-Photo from Frank Heath Collection.

Out of the gorge the descent of our train steepens, running down the slope of a vast

desert toward the distant Imperial Valley, which in the distance seems as unreal as

some of the closer mirages.

Elevation of 710 feet is lost in the nine miles from Carriso Gorge to dos Cabezas,

where today our train stops to pick up a waiting box car. The empty water car we

picked up at Tunnel 15 is set out beyond Dos Cabezas, at Coyote Wells.

Looking back, we can see the upward bend of the track we have just descended.

We roll on through Plaster City with the low sun burning red behind us, and set out

18 empty cars at Seeley to be taken by switcher to Plaster City for loading. The

gypsum plant there is one of our SD&AE's important customers.

Now the shades of evening are stretching in purple shadows across the desert,

as we leave the dry sands for the lush fields of the Imperials Valley.

The men of the SD&AE have completed another successful run.

(Photo at left) Engineer Ed Marshall brings our train into El Centre at the end of our spectacular ride from San Diego through Mexico and the Carriso Gorge.

November, Page 34

THANKS TO YOU!

Deserving Happy Retirement

MISCELLANEOUS

Jose Contreras, section laborer, SD&AE Railroad.

December, Page 3 and 4

A.T. Mercier Dies After Long Illness

ARMAND T. MERCIER, retired president of Southern

Pacific, died in Palo Alto, California, on November 21. The 76-year-old executive had been in ill health for several

months prior to his death.

ARMAND T. MERCIER, retired president of Southern

Pacific, died in Palo Alto, California, on November 21. The 76-year-old executive had been in ill health for several

months prior to his death.

Mercier served Southern Pacific more than 48 years. In 1904, following his graduation from Tulane University's

engineering school, he went to work for our company at Los Angeles as a rodman in a surveying gang.

On his 60th birthday, December 11, 1941, he became president of SP.

Under Mercier's leadership, Southern Pacific successfully carried its gigantic World War II freight and passenger

traffic, while serving more military establishments than any other railroad.

With the return of peace there fell to Mercier the job of restoring and modernizing a vast railroad plant worn by

years of war. He supervised the investment of hundreds of millions of dollars for new equipment including hundreds

of new diesel locomotives which virtually revolutionized train operations.

From his earliest days with Southern Pacific, Mercier was to know the meaning of service on a railroad's

battlefront, coping with flood, fire, wind and snow. In 1905-07, he participated in our railroad's dramatic struggle

to tame the Colorado river floods and save the Imperial Valley.

After wide experience in the engineering department, he was promoted in 1917 from division engineer at Los Angeles

to assistant superintendent of the Shasta Division.

Superintendency of the Portland division followed in 1918, and in 1921 he was appointed general manager of the

San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway. He became president and general manager of that line in 1927.

Two years later he was named vice president and general manager of Pacific Electric Railway.

He returned to the parent Southern Pacific in 1933 as general manager of our Pacific Lines.

In 1938 he was appointed vice president, Executive Department, remaining in that position until his rise to the presidency in 1941.

Serves as Director

After his retirement in 1951, Mercier continued to serve as a director of our company until October, 1954.

He is survived by his widow, Helen Ferris Mercier; two daughters, Mrs. Helen Polhamus of Palo Alto, and Mrs. Theodora

Paulman of Denver; a sister, Miss Aida Mercier, of New Orleans; and seven grandchildren.

Back to SP Bulletins

Back to SP Bulletins